Mary Ann's Teeth

As we already saw, Megalosaurus was the first dinosaur to ever be described by science back in 1824. It was also the first evidence that big predatory reptiles had once walked the land (giant marine reptiles had already been discovered before, with Ichtyosaurus being described in 1821 and Mosasaurus in 1822). Then in 1825 another paramount discovery would follow when British physician, geologist and paleontologist Gideon Mantell named and described Iguanodon (“iguana tooth”) based on several teeth and an incomplete skeleton. This time it was clear that this new prehistoric saurian was, unlike Buckland’s Megalosaurus, a herbivore. Or at least it was to Mantell, who very cleverly identified its remains, especially its teeth, as those of a huge plant-eating reptile from the Mesozoic era. Unfortunately for him, not every one of his peers agreed at first. French anatomist Georges Cuvier identified the teeth as those of a rhinoceros from the Tertiary, an opinion that he soon regretted on second thought but allowed other British scientists to mock poor Mantell for his error. Among them was William Buckland himself, who argued that the remains were not of Mesozoic origin, and thought they belonged to a fish.

However, upon later examination, Cuvier finally agreed with Mantell that the teeth and bones were of reptilian origin and belonged to a herbivore, and so did Buckland eventually, who still held doubts that the animal was a plant eater. Finally being proven right, Mantell sought to find similar teeth on a modern animal. He found a very close match (only twenty times smaller) on a preserved specimen of iguana that naturalist Samuel Stutchbury had prepared for the Hunterian Museum. Now he needed a name for his giant saurian. Initially he wanted to call it Iguanasaurus, but was reminded by fellow geologist William Conybeare that the name was redundant and could be applied to the modern iguana as well, so he suggested Iguanoides or Iguanodon instead. And so Iguanodon it was.

Mantell’s reconstruction of Iguanodon’s very incomplete skeleton, of which he made a sketch, depicted it as a giant lizard-like beast with a small pointy horn on top of its snout, which became a trope in all reconstructions of the era, including the giant sculptures Sir Richard Owen commissioned to sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to be exposed at the Crystal Palace in London. Later, more complete specimens showed that the “horn” was actually a modified thumb from the animal’s hand, a very characteristic trait of the Iguanodont family, but back then Mantell had no way to know and he just made an educated guess, probably based on the modern rhinoceros iguana (Cyclura cornuta) from Hispaniola, which has a somewhat similar outgrowth on its snout. But he was right on so many things that one must recognize his skill and ingenuity, given that he was really a medical doctor by profession who dabbled on geology, zoology and paleontology only because of his hunger for knowledge. He had no academic background in those areas, and yet he managed to become a recognized expert in all of them.

|

| Iguanodon sketch by Gideon Mantell. |

The

man’s actual job

as a physician, specifically an

obstetrician, leads me to the

origin of the remains on which he

based his description of

Iguanodon,

which is still debated and

has its own legend around it. Allegedly, by

his own account, the first Iguanodon

teeth were found by his wife Mary Ann,

who one day in

1822 decided to go with him when

he was requested to assist a woman that

was about to give birth somewhere in the

Sussex area.

While her husband worked, she went for a

walk through a nearby forest, which was

very close to a quarry. There

she noticed and picked up several fossilized teeth of significant

size, and brought them back to him, knowing

well of his

interest in fossils, unfolding a chain of

events that would lead to the discovery of a new animal for science.

However, this whole

story could very

well be a romantic tribute to his

wife rather than

a genuine account of the events.

At the time it was very

unusual for a doctor to take his wife with

him when visiting patients, and while it is

certainly possible, there

is no third-party evidence that he ever did such

a thing. Plus,

several years later, in 1851, he admitted

to finding the teeth himself, and he is

known to have been purchasing fossil bones from a quarry in Sussex as

early as 1819.

But it’s very possible too

that he was merely trying to undermine her

role, as Mary Ann had left him in 1839, allegedly

because of his

full-time

dedication to science. However, her

contributions to her husband’s work cannot be denied, as she is

responsible for the more than 300 illustrations that accompanied

Mantell’s papers.

|

| Iguanodon tooth drawing by Mary Ann Mantell. |

Gideon Mantell went on to describe the obscure ankylosaur Hylaeosaurus in 1833, and eventually became an authority on prehistoric reptiles and the geology of England. He continued to work as a doctor, but in 1841 he developed what was later diagnosed as scoliosis, which left him bent, crippled and in constant pain, and died in 1852 at the age of 62 from an opium overdose, a drug he’d been using as medication for his back pain for years. Whether it was an accident or he committed suicide remains uncertain. Whatever the case, he passed away before he could contribute to Richard Owen’s Crystal Palace dinosaurs, which is unfortunate, as by that time he had already realized that Iguanodon was not the bulky, elephantine beast that Owen was promoting, but actually had slender forelimbs. His passing allowed Owen to go on with his vision undisputed and his was the image of Iguanodon that became popular at the time.

|

| Crystal Palace Iguanodon models, by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (Wikimedia Commons). |

|

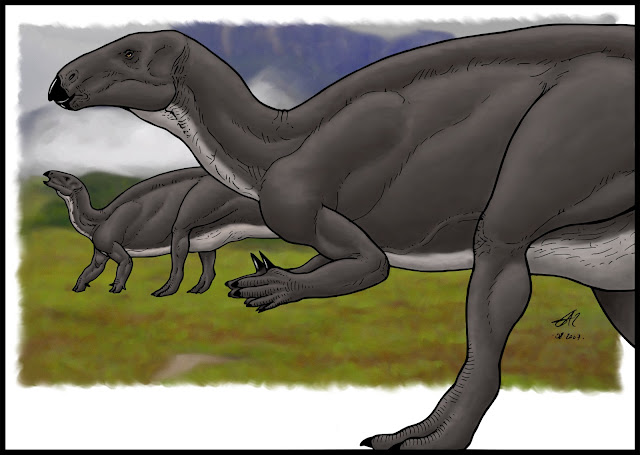

| My attempt at a slenderer Iguanodon, based on Mantell's vision. |

However, Mantell’s vision of this dinosaur as a more slender creature was confirmed later on, when 38 nearly complete Iguanodon skeletons were found in a coal mine at Bernissart, Belgium in 1878. Paleontologist Louis Dollo, who was in charge of studying and describing the specimens noticed, just like Mantell had done before him, that the animals had very slender forelimbs, and envisioned them as bipedal creatures that stood on their hind limbs like a kangaroo or wallaby. He also placed the spike that Mantell thought was a nasal horn correctly as a hand thumb. His vision of the animal, standing as a tripod and resting on its tail, became the standard for decades, despite the fact that he had to intentionally dislocate several vertebrae in the tail of the skeletons to make his mounts work.

|

| Skeletal reconstruction of Iguanodon by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, based on the Bernissart specimens (Wikimedia Commons). |

|

| Iguanodon model by Vernon Edwards, showing the now considered incorrect tripod posture. |

It wasn’t until the Dinosaur Renaissance, sparked in the 1960s by John Ostrom and his discovery of the small theropod Deinonychus, that dinosaurs began to be seen as active creatures closer to mammals and birds than to modern reptiles regarding their posture and activity level. This implied the idea that most (if not all) dinosaurs were warm-blooded animals that grew at a fast rate, took active care of their offspring, were capable of complex social behavior and in some cases could even be feathered like their close relatives and likely descendants, the birds. It also led paleontologists to reevaluate Iguanodonts and Hadrosaurs from the Cretaceous, and science started seeing them more as the cows of the time rather than gigantic plant-eating lizards. British paleontologist David B. Norman re-examined the Bernissart skeletons and noticed the ossified tendons that most likely kept the animal’s tail straight and parallel to the ground. This, in turn, made Iguanodon a convenient quadruped again, although one capable of casually adopting a bipedal posture and locomotion if needed. They also noticed they were able to chew their food instead of just swallowing it, which meant they probably had mammalian cheeks instead of long reptilian mouths.

|

| The Iguanodon from my childhood, as depicted on A Field Guide to Dinosaurs by David Lambert (1983). Artist unknown, although my bet goes to Graham Rosewarne. |

The Bernissart specimens were classified by Dollo as a new species, Iguanodon bernissartensis, as opposed to Iguanodon anglicus, which was Mantell’s creature. By being the better known one, I. bernissartensis became the type species of the genus, and therefore the main reference. Funnily enough, this led to I. anglicus being, upon later re-examination, considered different enough from the type species to be re-classified as the new genus Mantellisaurus. And so it happened that Mantell’s Iguanodon was… well, no longer Iguanodon, but a new genus that science named as a rightful tribute to the man who started it all. Paleontology is that funny and confusing sometimes.

About my Iguanodon piece, the one that starts this very post, it’s… okay, I guess. I got the proportions wrong, especially on the individual closer to the viewer. But I wanted to show the animal both as a quadruped and a biped, and that’s what I came up with. I wasn’t totally convinced about it even back then, but I was under a lot of pressure to finish all the illustrations for my book in time. I shouldn’t have bothered though, as it was never published anyway. I might make a new version of it one of these days.

That’s it for today. Take care and see you all very soon.

Comments

Post a Comment