Not a bird anymore?

|

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, when I was growing up, it seemed like every dinosaur book available to the general public (with few notable exceptions) had to have a section dedicated to other prehistoric animals that shared the world of the Mesozoic Era with them, most often marine reptiles (plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and mosasaurs), flying reptiles (pterosaurs), occasionally mammals and their relatives (synapsids) and almost always there was a subsection dedicated to Archaeopteryx (“old wing”). And there was a good reason for that. “Archie”, as it is affectionately known (or Urvogel -”primeval bird”- in German), was then universally considered both the oldest bird known by science and an important transitional fossil between reptiles and birds. It was fully feathered, had wings for arms, had big eyes and brain, and also had developed a wishbone, like modern birds. But it also had clawed “hands” on its wings, pointy teeth in its mouth, a long bony tail and a skeleton that looked a lot like those of small theropod dinosaurs of its time. Actually, an apparently featherless specimen was in a private collection for decades mislabeled as a Compsognathus, a contemporary theropod dinosaur not particularly close to birds. The similarities between Archie’s skeleton and those of theropod dinosaurs had already been noticed by English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley in the 19th century, shortly after the animal’s description in 1861, and he even proposed a direct evolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and birds, but his vision didn’t get support and would not be revived until a century later. Despite that, Archie became the perfect example of a transitional organism to support Charles Darwin’s ideas on evolution, in that it showed an intermediate stage between reptiles and birds. Such a convenient find led to some at the time deeming it a clever forgery.

|

| Compsognathus longipes, a small theropod dinosaur formerly considered to be closely related to Archeopteryx and birds. |

Archaeopteryx was a small creature, the size of a raven, that lived in the late Jurassic period (around 150 million years ago) in what is today southern Germany, at a time when Europe was an archipelago of islands with a tropical climate. It probably preyed on insects, other invertebrates and maybe small vertebrates too, and was likely capable of flying, judging by the asymmetric feathers on its wings and tail. Those feathers were remarkably well preserved on the specimens thanks to the limestone in which the fossilization process took place, which allowed scientists to see that they were virtually indistinguishable from those on modern birds, despite the animal’s other very reptilian traits. For decades, the consensus among scientists was that Archie’s similarities to theropod dinosaurs were due to a shared ancestry rather than a direct relationship between dinosaurs and birds, both evolving separately from an older group of archosaurs, then called “thecodonts”. It wasn’t until the Dinosaur Renaissance in the late 1960s that paleontologists like John Ostrom and Bob Bakker brought back Huxley’s idea that birds actually descended from theropod dinosaurs. Ostrom, who discovered and described Deinonychus in 1969, noticed that it shared more traits with Archaeopteryx than any of them did with modern birds. Archie even had the hyperextensible second toe with a “sickle claw” that’s commonly associated with dromaeosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinonychus, although significantly smaller. Bob Bakker got as far as suggesting that at least some small theropod dinosaurs would have been feathered, despite the lack of physical evidence at the time. Obviously, that’s what kept mainstream paleontology from endorsing such a revolutionary point of view, even as dinosaurs were increasingly accepted as active, warm-blooded creatures closely related to birds. The absence of feathers in dinosaur fossils kept Archaeopteryx firmly in its position as an early bird, as its feathers and long forelimbs kept it apart from its theropod relatives. And yet, some clairvoyant minds in the world of paleontology could clearly see the relationship between theropod dinosaurs and birds from the get-go, just like Huxley did more than one hundred years earlier. Artist and paleontology enthusiast Gregory S. Paul, who’s already been mentioned in this very blog, was one of those pioneers in the 1980s and 1990s. But John McLoughlin was drawing feathered theropods already in 1979. Talk about living in the future.

|

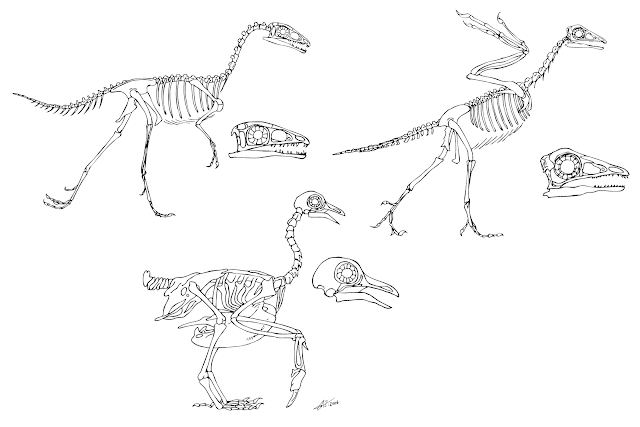

| Skeletal reconstructions of the dinosaur Compsognathus (top left), Archaeopteryx (top right) and a pigeon (Columba livia, bottom). |

Things changed significantly in 1996, when the small Chinese theropod Sinosauropteryx (“Chinese reptilian wing”) was described. Closely related to the aforementioned Compsognathus, and thus not among the closest relatives of birds, the new dinosaur was apparently covered in feathery integument, showing for the first time ever that at least some dinosaurs didn’t have a scaly, reptilian skin. However, Sinosauropteryx didn’t have wings, but small theropod arms just like its German relative Compsognathus. This, of course, allowed the most reluctant and conservative among paleontologists to stand their ground, arguing that maybe the integument that covered Sinosauropteryx’s body was not directly related to avian feathers, but could be some other structure, like a frill along the back similar to those on some aquatic lizards, that some paleontologists misidentified as feathers through wishful thinking. Or maybe it was a product of convergent evolution, just like the hairy structures that formed the coating of pterosaurs are not related to actual mammalian hair. And to be fair, they had a point. But since then, several other species of feathered theropod dinosaurs from the Yixian Formation in China have been discovered, all of them exceptionally well preserved, as is usually the case with specimens found there. Caudipteryx (“tail feather”), described in 1998, had unambiguous feathers on its tail and hands. While a much younger creature than Archaeopteryx, as it dates from the early Cretaceous period (around 125 million years ago), and thus too late to be a suitable candidate as an ancestor of birds, it is even more bird-like in some respects, with a shorter tail, a beak-like snout and only a few teeth at the front of the upper jaw. Its arms and the shape of its feathers, however, make it clear that it was a flightless creature, although it’s likely that it was a swift runner. Caudipteryx was a relative of the already known Oviraptor, which implies that the whole family were probably feathered.

|

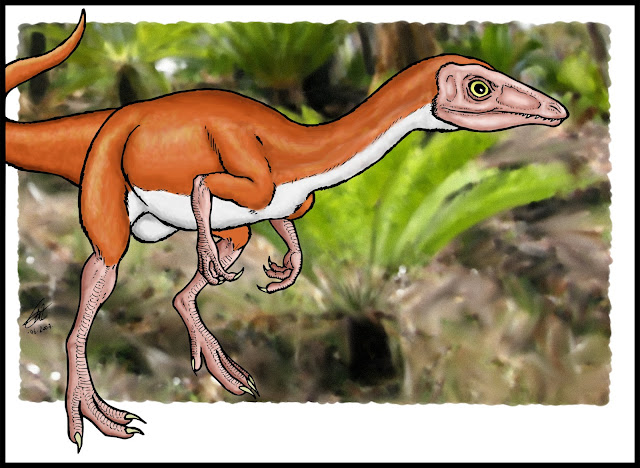

| Sinosauropteryx prima |

|

| Caudipteryx zoui |

If all that wasn’t enough (which it really wasn’t, as from a scientific point of view there’s no such thing as too much evidence), in 2000 the basal dromaeosaur (or “raptor”) Microraptor was described by Chinese paleontologist Xu Xing. Microraptor (“tiny thief”) was a small, more primitive relative of Deinonychus and Velociraptor, that had not one but two sets of fully feathered wings. Yes, the newly discovered freak of nature had functional wings formed by both its fore and hind limbs, and was probably able to fly using a very different movement pattern than those of the birds we know today. And just like the earlier Archaeopteryx, it had a fully toothed beak, a long reptilian bony tail, huge eyes and brain, asymmetrical flight feathers, a complete feathery covering, clawed “hands”, a “sickle claw” on its second toe… plus, a second, fully functional set of wings. How crazy is that? And what’s even more important: it being fully feathered proved that its later relatives, like the way more famous Velociraptor, Deinonychus and Utahraptor, were also bird-like, feathered animals, as feathers apparently appeared as a pretty early feature of coelurosaurs. Do you know who else is a coelurosaur despite its size? Yes, Tyrannosaurus rex. And although big animals rarely need much covering to retain their heat (after all, the biggest land mammals of today, like elephants and rhinos, are relatively “naked” creatures), it is very likely that T. rex chicks were fluffy little things when they hatched from the egg.

|

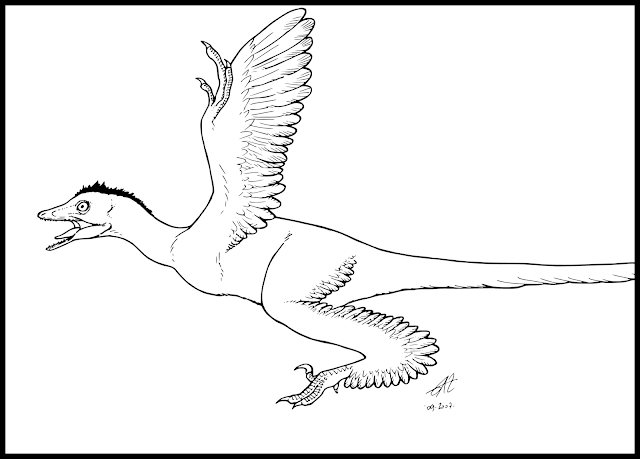

| Microraptor zhaoianus |

So many different blends of reptilian and avian traits on so many different dinosaur species made Archie’s position as the first bird somewhat dubious. The more feathered and winged dinosaurs were discovered, the less “unique” Archaeopteryx was by comparison, especially as other theropod dinosaurs seemed to share more traits with actual birds than what was considered to be the first bird until very recently. It obviously doesn’t help matters that the line between avian and non-avian dinosaurs has been blurred by such discoveries. The more you know about any particular branch of the evolutionary tree, the more difficult it is to draw the line between one creature and its closest relative. Considering all that, the consensus today is that Archaeopteryx is not really a direct ancestor of birds, but just another feathered theropod dinosaur closely related to their lineage. It is still a transitional fossil though, in that it proves, together with all other known feathered theropods, that birds evolved from dinosaurs and are, in fact, theropod dinosaurs themselves from a cladistic point of view. Thomas Huxley was right from the beginning. And so were John Ostrom, Bob Bakker, Greg Paul and all those paleontologists who took a bold stance with limited but very strong evidence favoring it.

It should be mentioned though that there are still some scientists that oppose the dinosaurian origin of birds, and defend that similarities between theropods and birds are not the result of a direct evolutionary relationship. American paleornithologist Alan Feduccia still considers Archaeopteryx to be an early bird, descended from basal archosaurs older than the dinosaurs, and thinks that later maniraptorians like dromaeosaurs and troodontids from the Cretaceous period are not really dinosaurs, but birds that lost the ability to fly and developed a terrestrial lifestyle, becoming bigger than their arboreal ancestors and acquiring characteristics of theropod dinosaurs by convergent evolution. So yes, according to Feduccia Velociraptor is a bird, not a dinosaur. But his vision has not been widely supported by paleontology and the consensus remains that birds are, from a cladistic point of view, deeply rooted in theropod dinosaurs.

That’s it for today. Take care and see you all very soon.

Comments

Post a Comment