The Second Age of the Giants

When I was a kid obsessed with dinosaurs, my favorite time period in the Mesozoic Era was the Late Jurassic by a mile. Sure, there was no T.rex, no Triceratops, no Velociraptor and no Ankylosaurus yet. And those are among many people’s favorite dinosaurs. The Cretaceous period is the one that gave us the most popular dinosaurs. But the Late Jurassic was The Amazing Age of the Giants for me. It was the time of the giant sauropods: the long and slender Diplodocus, the bulky but muscular Brontosaurus, the colossal Brachiosaurus. The time of the plated herbivorous Stegosaurus, with a weight of 3.5 metric tons and a brain the size of a walnut. Those herbivores shared the land with the mighty Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus, animals that, while not as big and robust as a T. rex, were apex predators nonetheless that herbivores of the time had all the reasons in the world to fear, especially the young or sick.

It was also a time of heavy contrasts. The biggest dinosaurs shared their world with the smallest ones, like the tiny Compsognathus and the fully feathered Archaeopteryx, a creature that back when I was growing up was thought of as the oldest known bird. But as birds had yet to flourish and diversify, pterosaurs dominated the skies, and plesiosaurs and icthyosaurs thrived in the oceans.

On land, there were also herbivores of a more modest size than sauropods, like the ornithopod Camptosaurus; and also medium-sized predators like the agile and fast Ornitholestes, which was more often than not depicted hunting down Archaeopteryx in the books of my time.

During the Cretaceous period, sauropods were gradually replaced by other herbivores like hadrosaurs and ceratopsians; large allosauroid theropods handed over their place of apex predators to tyrannosaurs, and ankylosaurs took on the role of stegosaurs… or that’s what I thought growing up. While that narrative is mostly true for the Northern Hemisphere, it was a very different story in the South. Keep in mind that popular books of the time were scarce in dinosaurs from South America and Oceania, with most species depicted coming from North America and Asia, a few from Africa and Europe, and anecdotal mention of South American titanosaurs. It wasn’t until maybe the late 1990s or early 2000s that I found out that my very dear landscape of the Late Jurassic of North America had a “sequel” of sorts in South America that lasted for a good chunk of the Cretaceous. I know what I’m saying makes no actual sense, but please bear with the child inside of me.

Through online sources (like the defunct DinoData and Dinosauricon, and some other websites I can’t remember anymore) and a book that my brother in law brought for me from a trip to Argentina (which turned out to be the local edition of the Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life by David Lambert, Darren Naish and Elizabeth Wyse, originally published in the UK by DK Publishing in 2002, with added content by Argentinian paleontologists José Bonaparte and Sebastián Apesteguía, and additional art by the magnificent Jorge Blanco and Luís Rey), I finally came to know that allosauroid “carnosaurs” and the amazing sauropods kept flourishing in the Southern Hemisphere, joined by other kinds of interesting dinosaurs that had mostly died out in the North. And they actually got way bigger, meaner and cooler than they had ever been anywhere else.

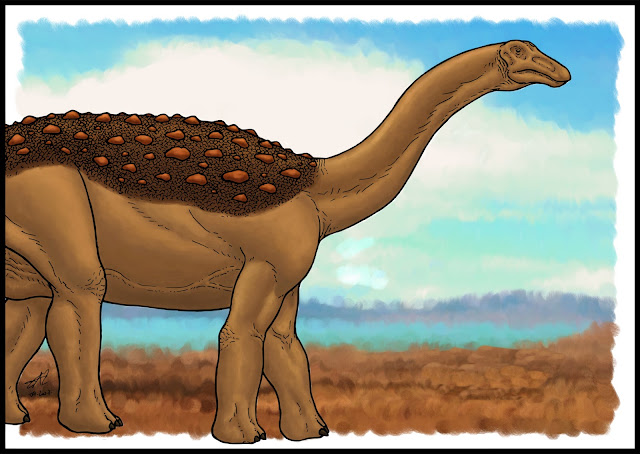

I already knew about a few sauropods from South America, but their remains were fragmentary and they seemed to be rather unremarkable creatures (for a child) compared to their huge Jurassic relatives from the North. Except for, maybe, the once ubiquitous Saltasaurus, which, despite being pretty small for a sauropod, was the only one known to be armored. This animal used to be a staple of dinosaur books in the 1980s, but it seems to have fallen out of favor at some point.

|

| Saltasaurus loricatus, a relatively small armored titanosaurian sauropod from Argentina that used to be a staple on 1980s dinosaur books. |

However, finding out in the early 2000s about such remarkable creatures like the giant sauropods Argentinosaurus and Patagotitan, allosauroid predators like Mapusaurus and Giganotosaurus (which rivaled T. rex in size and maybe even surpassed it) weird abelisaurian theropods like Carnotaurus and Abelisaurus, and local dromaeosaurs (“raptors”) like Buitreraptor, painted a wholly different picture of the Late Cretaceous period that felt indeed like a sequel of the Late Jurassic of North America in my still childish mind (and you probably should know that I was already in my 20s by then, but my inner kid has always been tough to kill).

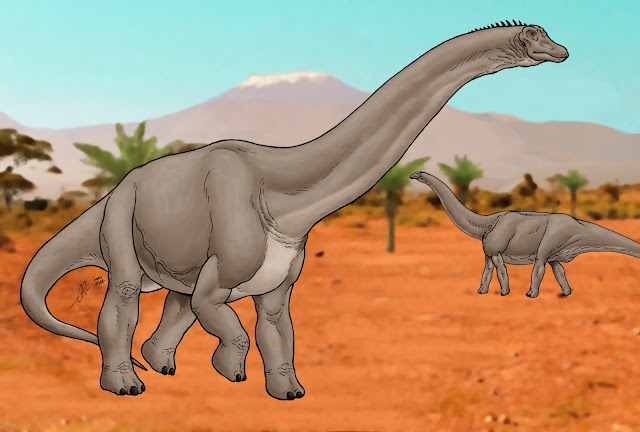

It’s true that the remains of titanosaurian sauropods are still very incomplete, but newer discoveries have given us enough information to know that they were the biggest land creatures known to have ever existed, and that they were closely related to brachiosaurs and camarasaurs. However, one can see a lot of discrepancy among paleoartists on how these animals are depicted, as skull material is really scarce and they’re mainly known by limb and pelvic bones and some vertebrae. This, of course, makes the size estimates vary wildly too, but it’s pretty clear that Argentinosaurus and its closest relatives were among the largest and heaviest animals to ever walk the Earth.

The existence of such gigantic herbivores implies that of accordingly big predators, which that role being played by carcharodontosaurids like Mapusaurus (which co-existed with Argentinosaurus) and the closely related Giganotosaurus, bigger relatives of the North American Allosaurus that may have surpassed Tyrannosaurus rex in size, even if they weren’t as bulky and had a weaker bite. They eventually got extinct well before the end of the Cretaceous, being replaced by the smaller abelisaurs and the poorly known megaraptors.

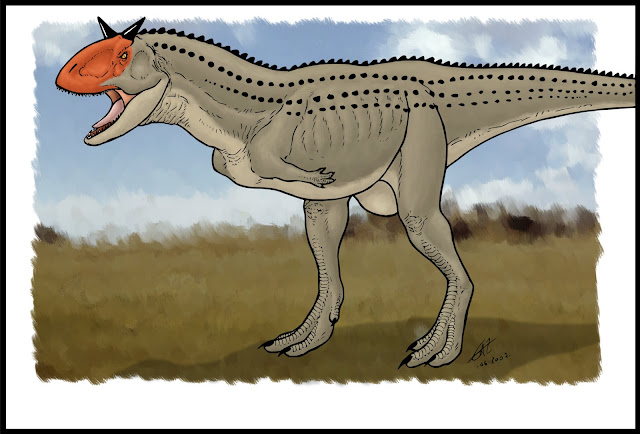

|

| Big and mean Giganotosaurus carolinii. Again, the "bunny hands" are incorrect. I am going to re-draw all these creatures at some point. |

Those abelisaurs were distant relatives of the ceratosaurs of the Jurassic. They were weird medium-sized predators with short faces and small, vestigial forelimbs with very short (and fused) forearm bones and no elbow mobility, the most well known of which is the horned and pug-faced Carnotaurus. I remember learning about Carnotaurus through a trading card collection from the early 1990s, so it was well before I knew anything about most South American sauropods and allosauroids. It surely was not on any of the dinosaur books I owned growing up, and it certainly made me aware that my vision of the Mesozoic Era was too centered on North America and Asia (again, the Northern Hemisphere), with very few animals from other continents (Europe was a chain of islands for most of the Mesozoic, so it’s understandable that dinosaur remains are comparatively scarce).

But there was an explosion of very important discoveries in South America (mostly Argentina) and Asia in the late 1990s that would change the paradigm of popular books on dinosaurs forever, by expanding our vision of dinosaurs themselves as a group, as well as forcing a more bird-like image of theropod dinosaurs into the public, especially after many new feathered species were described based on exceptionally well preserved specimens from China. And that’s definitely a good thing. I was recently browsing through my collection of dinosaur books from back in the day, and I actually was surprised at what a narrow vision of dinosaurs they offered by today’s standards. And those are all post-Renaissance books that incorporated most of the revolutionary ideas of pioneering paleontologists like John Ostrom, Bob Bakker and Jack Horner, meaning that they offered a modern vision of dinosaurs as active, warm-blooded, socially complex and bird-like animals, in contrast with the traditional vision of huge sluggish lizards destined for extinction. But they lacked a wider geographical view, one which has fortunately become the norm nowadays. Of course it was not an intentional thing, as most of the revolutionary discoveries from Argentina and China just had not taken place yet.

Coincidentally, both continents were home to a very peculiar family of small, very bird-like dinosaurs called the Alvarezsauridae, named after Argentinian historian Gregorio Álvarez, and while members of the group were initially found in both Argentina and Mongolia, later discoveries were made in North America and Europe, suggesting the presence of land bridges between all those continental masses at certain points in the Early Cretaceous period.

|

| Shuvuuia deserti, an example of alvarezsaurid. This one's from Mongolia, but they all shared the same basic body plan. |

Going through my collection of old books, even if it initially had the only purpose of reminiscing about my childhood, has made me even more aware of how much our image of dinosaurs has changed over my lifetime, not only because we know a lot more about their anatomy, behavior and evolutionary relationships, but also because the geographical scope of paleontology and popular media has widened accordingly. It also makes we wonder how many new findings await us in the future, how much will they change our image of dinosaurs, and which unexpected places will become new cradles of discovery. My inner child will be there as usual, anxiously waiting for new knowledge to absorb.

That’s it for today. Take care and see you all very soon.

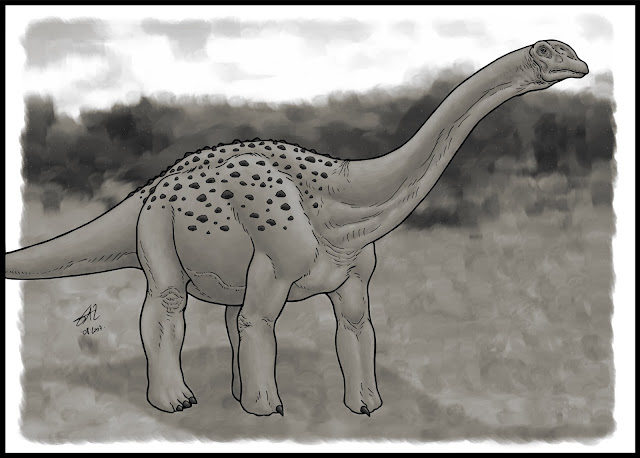

|

| Antarctosaurus wichmannianus, another South American titanosaur that used to feature on all dinosaur books from the 1980s. Now it's considered a dubious genus. |

Comments

Post a Comment